1. Introduction

I’ve defended utilitarianism in the past, but just because I’ve defended an ideology does not mean I support it. Admittedly I still lean towards consequentialism, but just as it is important to understand the strengths of any given position, so too is it important to understand its weaknesses.

For the sake of argument, I’ll be addressing forms of utilitarianism insofar as they prescribe to maximize utility rather than minimize suffering. Utility can take either its classical or preference-based definition, for utilitarianism still suffers immense blows in each form.

With that out of the way, let’s begin attacking the idea that we need to maximize the greatest good for the greatest number.

2. Counterexamples and Common Sense

Counterexample #1: Exploitation

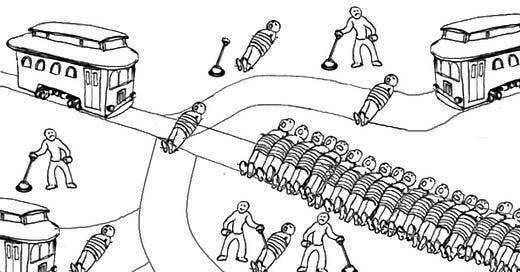

It seems a lot of, if not most, counterexamples of utilitarianism follow the same structure: an act that maximizes utility inadvertently causes the violation of the consent of one or many individuals. It’s not hard to find some examples:

a. Let’s say you’re a doctor looking after 5 ill patients, desperately in need of different organs, but without any hope of receiving said organs. Miraculously, you have another patient walk in, who is a perfect match for all 5 patients who need organs.

b. Suppose you’re a sheriff and the only way to prevent a riot that kills hundreds of people is to frame an innocent person.

Standard act utilitarianism requires treating a human being as a means to an end in both scenarios, going against the prescriptions of deontology and basic moral intuition.

Of course, the typical utilitarian reply is to mention that rule utilitarianism rules (pun intended) violating consent out of the picture, because allowing so would reduce utility at the aggregate. But if that were the case, in “an applied sense”, what would differentiate it from deontology?

If one were to instead bite the bullet, and say that treating someone as a mere means to an end is permissible, how would one reconcile that with the intuitions of most people?

Counterexample #2: The Experience Machine

Robert Nozick offers a famous hypothetical, an individual is given a choice between two options. One allows you to stay in the real world and the other allows you to enter the experience machine, which would stimulate a life with higher well-being.

At the individual level, classical utilitarianism implies that one should enter the machine, but Nozick objects. After all, exiting real life ends the opportunity to experience truth and authenticity that a couple more utils can’t afford.

If one would seriously consider not entering the experience machine, then classical utilitarianism faces a severe problem: aren’t there things that together make up greater importance than happiness?

Counterexample #3: Dawn of the Dead

Okay, okay. Let’s try to take a pluralistic view. Maybe happiness isn’t everything after all. Let’s consider preferences instead, allowing individuals to consider their own range of values in whatever order they want.

But what if p-zombies (people without consciousness) existed? These zombies can state preferences and, if rational, even have utility functions. It seems obvious that preference utilitarianism gives them moral consideration. Yet, why should it?

Zombies don’t experience consciousness, so why are they given ethical concerns? Well, why don’t we just stop factoring in zombie preferences? But how would that work? After all, p-zombies are indistinguishable from regular human beings.

In a world with zombies, preference utilitarianism could not just dictate the violation of consent, it could also end up not maximizing non-zombie utility, whether preference-based or hedonistic.

Further, what compels us to take into account the preferences of the dead? Of course, in most cases, not doing so would violate the categorical imperative, and thus contradict rule utilitarian goals. But from a hedonistic viewpoint, the only reason to respect the wishes of the dead is so that the living will have confidence that their wishes are respected. Otherwise, why respect them at all?

It seems that the problem of unconscious beings expressing preferences is not the only one that preference utilitarianism has to bear. The inverse is also true. Beings that are unable to express rational preferences (e.g. non-human animals) still experience pain and pleasure, yet preference utilitarianism only takes them into account insofar as they are of value to “rational” beings.

If there are good enough reasons against classical utilitarianism (the experience machine) and good enough reasons against preference utilitarianism (zombies and irrational preferences), then why be a utilitarian at all?

Counterexample #4: To Infinity and Beyond

Suppose that in consideration of all of space and time, there are an infinite amount of lives, each with positive utility on average. Even with a discount rate, the sum of total utility would be infinite. But wait, doesn’t that present a problem to utilitarianism?

If utility is infinite, then it would also be maximized. Thus, reducing moral suffering or “increasing” utility doesn’t change utility because it’s already infinite. There is no numerical difference between an infinite amount of one-dollar bills and an infinite amount of five-dollar bills, they’re both an infinite amount of dollars.

Infinity is not a process where you count and count and eventually you get there, it’s a process of looking at all of it at the same time. So long as the conditions for infinite utility are met, then utilitarianism cannot differentiate the moral worth of any actions that don’t threaten the conditions, all of them lead to the same utility.

That means so long as we’ve hit infinity, there’s no need to comply with consent, no need for effective altruism or Singerian moral obligations, and even no need to maximize individual utility.

Indeed, the conditions for such a scenario aren’t hard to conceive of. One could imagine a multiverse or an infinite amount of planets. More realistically, to achieve infinite utility, one could simply require a few conditions:

The average utility is positive

Continual reproduction

No existential risk

The only condition that reality hasn’t almost certainly been met is no. 3, and even that isn’t very unlikely in and of itself. Even having a high social discount rate would still allow for infinite utility to be achieved.

Whichever way it happens, infinite utility means that not only is utilitarianism unuseful as a moral yardstick, but it also has little applied normative goals.

That alone suffices to say utilitarianism as an ideology is almost meaningless.

Counterexample #5: Common Sense

Okay, let’s say that in the edge cases, you bite the bullet. Let’s say you enter the experience machine unless it violates your preferences. Let’s say zombies and non-human animals pose problems in almost all moral ideologies. Let’s say that exploiting others is sometimes morally permissible.

Does that still allow for all the moral obligations that utilitarianism imposes upon you? Does that mean we should all live like saints and worship the Against Malaria Foundation? Does that mean we should all have rational preferences and study decision theory? Does that mean we should help others if the benefit they receive is slightly higher than the cost we incur even if we really don’t want to?

Common sense tells us we should consider what most people think. But we don’t need to ask most of the population what they think to know what it is, we just need to look at what they do.

3. Isn’t this just deontology?

Fine then, assume that after all these counterexamples you’re still a hardcore “Bentham enjoyer” or “Hare enjoyer”. Take it that infinite utility is a goal, not an assumption.

Still, should distinguish this from say deontology or any other reasonable moral theory for that matter? If one says that “freedom” be maximized and the other says utility should be, how do they differ from the perspective of applied ethics?

In most cases, utilitarianism, deontology, and contractarianism all seem to converge on the same position. Utilitarianism need not offer more moral obligations than other ideologies either, Christianity and Kantian ethics are fairly strict as well. If rule utilitarianism doesn’t bite the bullet in edge cases, then what differentiates it from typical deontology?

If you’re an act consequentialist or a two-level consequentialist, see the above.

4. How do we even calculate utility?

Maybe utilitarianism need not be our moral guide. As R.M. Hare has noted, we can combine ethical systems in such a way that while other ideologies may act as tools, they can all serve the purpose of maximizing utility, what utilitarianism prescribes.

In other words, utilitarianism could just be a destination rather than a map. But how do even we calculate utility? Interpersonal utility comparisons can’t occur, so that’s off the table. Measures of happiness are imperfect and can negate rational preferences, so that’s out of the way too.

What about Kaldor-Hicks benefits? Shouldn’t their maximization be the goal? Well, if we were to give $2k in real wealth to Donald Trump and take away $1.9k in real wealth from a poor person in a developing country, have we really increased utility?

If the goal were to maximize Pareto improvements, what would separate this from any other ideology? Saying “Pareto improvements are good” isn’t exactly a unique or notable idea.

Of course, a simple idea would be to base our moral considerations on the preferences of a hypothetical rational agent who experiences all of consciousness, but at that point, objectivity is simply dead.

Regardless, this all leads back to the same question. Even if utility maximization was the destination, if some other ideology was used as the path taken, what distinguishes utilitarianism from that ideology?

5. Counterexample #6: Cowen’s Dilemma

All of my criticisms so far cannot stand up to a utilitarian’s biggest defense: the idea that utility maximization is simply what should be aimed for, even if it counters our moral intuitions and even if it is hard to conceive of or achieve.

But Tyler Cowen often presents an excellent dilemma against utility maximization. It roughly goes like this: suppose you are offered a choice between having C utility and a lottery with probability A of having B*C utility and probability (1-A) of having 0 utility such that A*B*C is greater than C.

Cowen presents the case as a double-or-nothing scenario where the probability of getting double the risk-free expected value (or utility) is 51%. The principle of maximizing expected value/utility dictates you always take the option with a chance of no utility. Of course, if you continue to do so on and on, you are almost certainly ending up with nothing.

This one counterexample is all that is needed to destroy the foundations that utilitarianism stands on. So if utilitarianism is not only useless as a map but also as a goal for territory, what does it really have to offer?

6. Conclusion

In the end, I’m still standing as a bullet-biting consequentialist. I don’t think most of these counterexamples drastically change my viewpoint about utilitarianism because, simply put, all other ethical theories seem to raise more objections than this particular one. But if you’re going to take a position, you ought to understand all the holes it has. And before we embrace the greatest good for the greatest number, we should first look before we leap.

Admittedly, this post was a bit rushed, especially the bit on infinity and all (please don't kill me). Still, it was to fun to "take down" a view I hold myself. Might post "The Case Against The Case Against Utilitarianism" in the future.