Why do some nations fail and others prosper? Why do some countries grow rich and others poor? Why do some countries without natural resources go to the first world and others born in abundance go to the third?

Economist Daron Acemoglu and political scientist James Robinson can answer these questions in one word: institutions. According to their theory, that is the best monocausal explanation of history. If culture or geography were a better explanation, why is there such a magnificent difference between North and South Korea?

Acemoglu and Robinson come back again: it's the quality of the institutions. Back in the 1950s, neither were democracies, one had a liberal free market, and the other was a communist state.

Today, one of those countries is a thriving first-world liberal democracy and the other is North Korea.

The institutions provide the gateway towards poverty and prosperity. Institutions can be classified as economic or political and inclusive or extractive, and they guide the incentives for moving a country through the narrow corridor that leads to abundance. If incentives are misplaced, so is trust in the institutions and the rule of law itself

Democracy leads to economic growth. So does free trade. So does education.

But what leads to these institutions? Good politics. Good governance.

But what leads to good governance? Good leaders.

Good leaders must be intelligent so that they know how to guide their people, but they must also be benevolent so that they can fight for their people.

Both of these men were born in September between 1915 and 1925. Both studied law at an elite college. Both served as leaders of their countries for over 20 years. Both led Southeast Asian countries born out of poverty and imperial reign.

But one country is not in the third world anymore and the other is the Philippines. One country had an abundance of natural resources and the other was Singapore. One country had a dictator who was greedy and the other had an authoritarian leader who was benevolent.

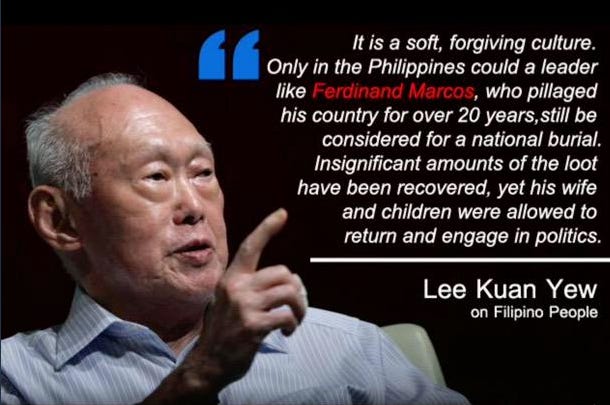

Lee Kuan Yew (LKY) threatened his opponents merely with defamation lawsuits and prison sentences. Marcos tempered directly with the ballots himself. Both men opposed communism, but one created conditions for liberal democracy and the other for kleptocracy.

LKY instituted free trade, open immigration, tax cuts, and massive infrastructure and education projects. English became the working language and pollution would go penalized. You could define Singaporean economic policy not so much as liberal but as staunchly pragmatic.

In contrast to the corruption-free technocracy, the Marcos regime was a brutal one built on disinformation and extractive institutions detrimental to growth. Martial Law was upheld and billions upon billions of pesos were taken from the people to serve the elite.

You may think, contrary to all evidence, that LKY was a liar and Marcos was honest, but GDP numbers don’t lie, and for all the similarities between Singapore and the Philippines, income per capita is not one of them.

In the start, the Philippines had more resources and a bigger population, and in the end that still remains true. But Singapore remains the greater country because it was gifted with inclusive institutions and the Philippines was tormented with extractive ones.

This ends as a parable of more than just institutions. It ends as a tale of what leaders can do to a nation. No matter how intelligent and conscientious a leader is, the difference between the third world and the first can come down to the simple difference between greed and benevolence.

Very profound.